By William Ruffin, Farm to Table Guam Volunteer

Disclaimer: This article does not deal with municipal size composting (which Guam ought to have!) nor anaerobic composting (composting without air) nor ‘bokashi,’ which is a special kind of anaerobic composting (from Japan) that can deal with meat along with the green waste. You can learn about these methods on the Internet.

What is Compost?

When people say it, they usually mean finished compost, since composting is the process of natural recycling that dead organic matter (leaves, twigs, leather, fruit, etc.) goes through as it is slowly changed into finished compost.

Finished compost is a free, natural, slow-acting fertilizer, ready to be used to help your plants be healthy and stay healthy.

Uses of Finished Compost

- Used on the ground around plants.

- Mixed into the red soil up to 50% (more than about 50% causes the soil texture to resemble the texture of mud).

How does composting happen?

Composting is natural and is always happening; but very slowly, and only in a very thin layer on the ground where good bacteria and fungi are at work on the natural mulch (organic matter), changing it into finished compost. It is what turns the top of Guam’s red soil brown, little by little.

Hazards of Store-Bought Fertilizers

- Because they’re fast-acting, they run the risk of overdosing → which is why they require the users to read, understand and follow the instructions on the containers.

- Run-off of the excess fertilizer can pollute streams, reach the ocean, and increase growth of algae, resulting in smothering coral.

- Store-bought fertilizers do not increase the ability of the soil to hold water.

Ways to Recycle

- Kitchen waste

- Green waste, no meat!

- Bury small amounts (up to a gallon) bury it in your garden in a hole you dig.

- The composting process will happen underground.

- Next time you accumulate a gallon of kitchen waste, dig another hole in a different place, perhaps next to the first hole.

- Green waste

- Use worm composting which has been popular to create finished composting. Tip: use worm manure, which also can be bought in garden supply or hardware stores for use as fertilizer.

- ON GUAM → Bernice Nelson of Amot Taotao Tano Farm on Swamp Rd., Dededo, does worm composting on a large scale; and I think she teaches the method, and sells the special earthworms (“red worms”) used.

- ONLINE → You can search online to learn how to buy or build a worm composting box that fits under your kitchen sink and learn how the simple process works.

- Yard waste

- You can add your kitchen waste together with your yard waste

Containers to Use when Composting

- Plastic

- Metal

- Fencing material

- Wooden, untreated pallets

The most efficient kind of compost container I have seen is a 55 gal.oil drum suspended 4 ft. high horizontally. It has an axle through the two flat ends, one of which has a handle for rotating (mix) the whole container; and there is a little door in the curved side where you can put in green waste or take out finished compost. But a container is not needed, especially if you have a larger amount of green waste (leaves, twigs and kitchen waste) to recycle.

DIY Compost Containers

If you make your own, make it the ideal size for manual composting: 4’x4’x4′. This size is manageable with a spading fork or manure fork (they both have flat tines). Local hardware or garden supply stores may have one or more models of compost containers on display.

The easiest way to create a larger amount of finished compost is to use the pile method.

The Pile Method

- Choose a place in the shade of a tree (where rain will fall).

- Begin to toss all your green waste there.

- When the pile is at least about 4 ft. tall (may take weeks), start to count the months from that date

- Continue to add green waste since you will be harvesting finished composting from the lower middle of the pile (unless you are actively composting) which is not hampered by continuing to add material to the top of the pile.

- Depending on the amount of moisture in the pile and your patience, after 3-4 mos. dig into the lower middle part of the pile with your spading fork to see how much finished compost has formed

- If there is enough for your garden needs then harvest it.

- If not, then leave it there and fill up the opening and wait another month or several, to inspect the middle of the pile again.

- Repeat, forever.

More efficient than a pile is a bin.

The Bin Method

- A bin is formed by 3 wooden pallets to make an enclosure that is open on the top and the front, and is close to the ideal size for composting without machinery: 4’x4′ by at least 4′ tall.

- Concrete blocks can also be used, placed on their sides to allow easy air flow.

- Then add green waste constantly, just as you would in a pile

- When the bin is nearly full, start counting the months from that date

- Dig into the middle to check for enough finished compost, etc. just as you do in a pile

Tips in Bins

- A bin is much easier than a pile to actively work with; in fact a pair of pallet bins, side by side (needs 5 pallets, and wire to hold them in position).

- Stop adding material when the bin is nearly full, then fork the whole bin into the 2nd bin, making your observations as you go.

- Soak it and wait another interval.

A bin makes it easy to notice the reduction of volume at each interval, if the process is working.

The Pile Method and Bin Method are ways of passive composting (except the rotating metal drum).

Process of Active Composting

Active composting involves more work since you are keeping an eye on the process, tending it, and refining it to make more finished compost in a shorter time. The heat that develops in the mass of ingredients, if hot enough, kills pathogens and any seeds of weeds.

One of the biggest differences from passive composting is that when the ingredients (green waste) you are adding reaches the amount you want to work with, you STOP adding any more.

Then the whole bin or pile will finish at the same time, and be ready to use–because you will have mixed (turned) all of it enough times until the whole mass has turned to finished compost, and will not be warm to the touch any more.

If the green waste is used (as slow-release fertilizer) before it is finished, it can damage (“burn”) your plants! I speak from sad experience.

Also, active composting allows you to easily notice that the amount of finished compost is only about a third of the amount of green waste you started with. (The same reduction in volume happens when passive composting, but it is hard to notice, since you are constantly adding green waste.)

All composting is best done in a shady place, since the green waste should ideally be kept “as wet as a wrung out cloth” and direct sunlight tends to dry out whatever it touches, so it will slow down the process.

Browns vs. Greens

It is useful to think of the ingredients of compost as either “Browns” or “Greens.”

“Browns” are actually brown in color and include:

- Dead leaves

- Twigs

- Wood chips

- Sawdust

- Bark

Many “Greens” are not actually green and can include:

- OLD manure (=”tempered”= aged about three weeks, from plant-eating animals)

- Kitchen waste

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Flowers

- Green grass

- Green leaves

The process of composting needs both, but MUCH more Browns than Greens, and in the proportion of 10:1 or 30:1

But don’t worry about the numbers!

Here is how I dealt with the proportions when carrying out my longest and most successful composting experience (in Tiyan, working with Island Girl Power):

Since there is an unlimited quantity of cut grass in Tiyan, I used it for my “Browns,” about seven trash bags of it (I was doing active composting, using the three-bin system), plus two or more 5-gal.buckets of kitchen waste, and about 3-4 buckets worth of tempered horse manure (if I could get it) for my “Greens”. When I had gathered all these ingredients I began to stack them in layers in the bin: A six inch layer of dead grass, 3 inches of the manure, another six inches of the grass, a 5-gal bucket of kitchen waste, and six inches of the grass, repeating this sequence as much as practical, by keeping an eye on evenly distributing the ingredients throughout the stack. The lower grass layers would get smashed down to much less than 6 in. due to the weight of the material above. When the grass was used up, the stack would be 5-6 feet tall. Then I would soak it with a hose for 10-15 min. trying to get all parts wet. Then, if the days were hot and dry, I would cover the stack with a tarp to slow down the loss of water. A week later when the kitchen waste (which I had kept about three in. away from the edges of the stack, to make it harder for rats or other vermin to get at it), had a chance to start to break down, I would fork all of the material into the next bin, observing what had or had not started to break down, and how fast; especially the food waste, which I’d had to cut into smaller pieces before adding it to the stack. I could then make decisions about how small to cut future kitchen waste; I could feel the temperature with my hand, hoping it was hot in the inner areas at least, and note the presence of the masses of white threads (fungal mycelia) that mean the process is proceeding fast. Was the material “as wet as a wrung out cloth”? All such observations told me how to constitute and treat the next batch of green waste, what to add more of or less of. Then I would soak the stack ten min. or so, cover it or not, depending on the amount of rainfall expected, wait another week and then move it all again into an empty bin, making all the observations as I work. In four to five weeks the result would usually be about a cubic yard of black gold! This is the heart of active composting! It is a learning process, as the availability of different ingredients changes, the weather changes, etc.

Work in Smaller Pieces

The speed of the process is faster if the ingredients are in smaller pieces.

Things you may need:

- A machete and some kind of cutting board is useful for cutting handfuls of weeds into a maximum of 6 in. lengths.

- Without a machete, a pruner or one of those heavy duty scissors may be needed.

Fruits and veggies should be cut into pieces. How small depends on what you observe when you turn the ingredients weekly, each two weeks, monthly, or however often you like. Air is needed for hot, fast active composting. This is why bins have holes or slats in their sides and why pallets are convenient to use for bins.

Use pallets of untreated wood, if you are growing food plants.

Easiest Way to Actively Compost

- Stop adding material when the pile is as high as what you want to work with (it will lose two-thirds of its bulk as it turns into finished compost, so start with a pile as tall as you can manage).

- Then, at the regular interval you decide on, fork the whole pile into the empty space beside it, observing the progress as you work.

- Then soak it and wait another interval, covering it with a tarp if heavy rains are expected, since bad smells can result from too much water (which reduces the air available for the process).

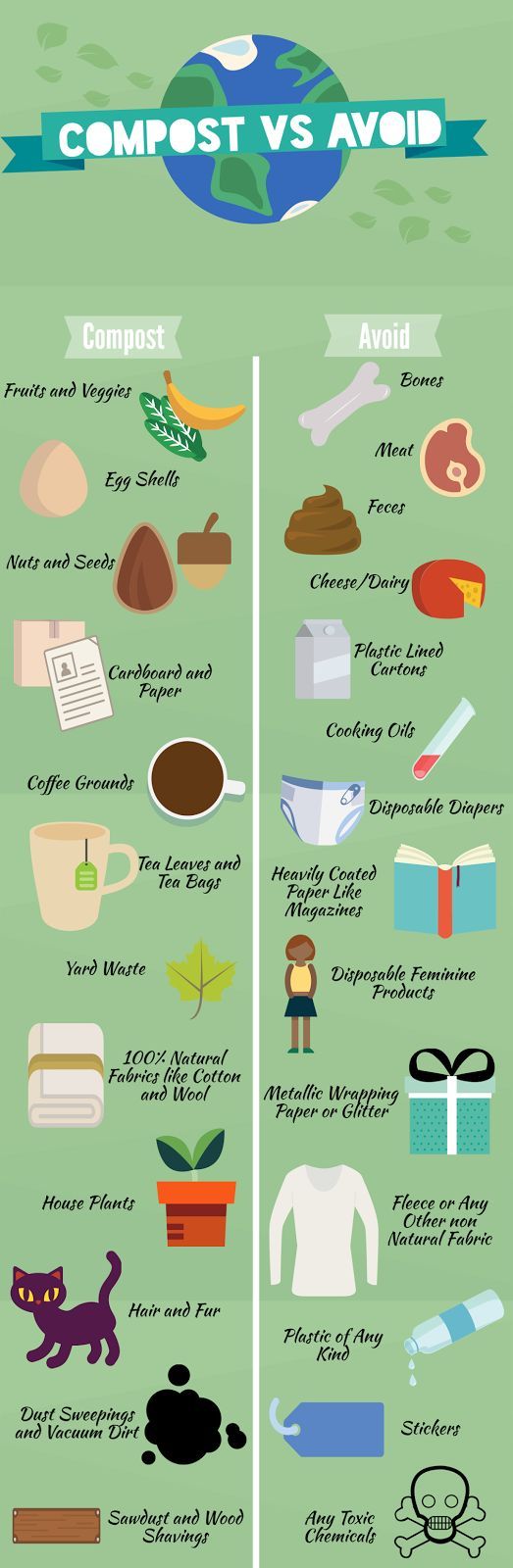

All organic matter is compostable, if the conditions are right. Some organic matter is difficult, unpleasant, unsafe or illegal to compost in urban areas.

Do’s and Don’ts of Composting

- Eggshells are a nuisance as they take so long to break down. But when they are in the material I use, I crush them as small as practical before including them in the process.

- The peelings of oranges (and I think all citrus fruit peels) resist the process, but I have found that by cutting them in pieces of about an inch, they compost fine.

- Greasy, oily stuff also resists, so I don’t include it in bulk (butter, mayonnaise, etc.)

- I also exclude dog and cat waste and human waste too, although it can be composted but in order to be completely safe, it must compost for a period of 4 years.

Start Composting on Guam today!

In the tropics the red soil is so poor that it should not be added to the compost. Here in Guam, horse manure can be bought for $20 per pickup truck load (you load it yourself).

I can be contacted through Farm to Table farm, where I work (with a chipper/shredder machine!) as a volunteer composter. We use the three-bin system, which is used in most community gardens across North America.

There is lots of literature about composting. It is not “rocket science.” But I have not seen any instructions on dealing with palm fronds, ironwood, or pandanus “keys” (which get stuck in chipper machines).

It would please me if I found out that even one person was inspired to start composting after reading this, and if you find new ways of dealing with these types of compost, please let me know.